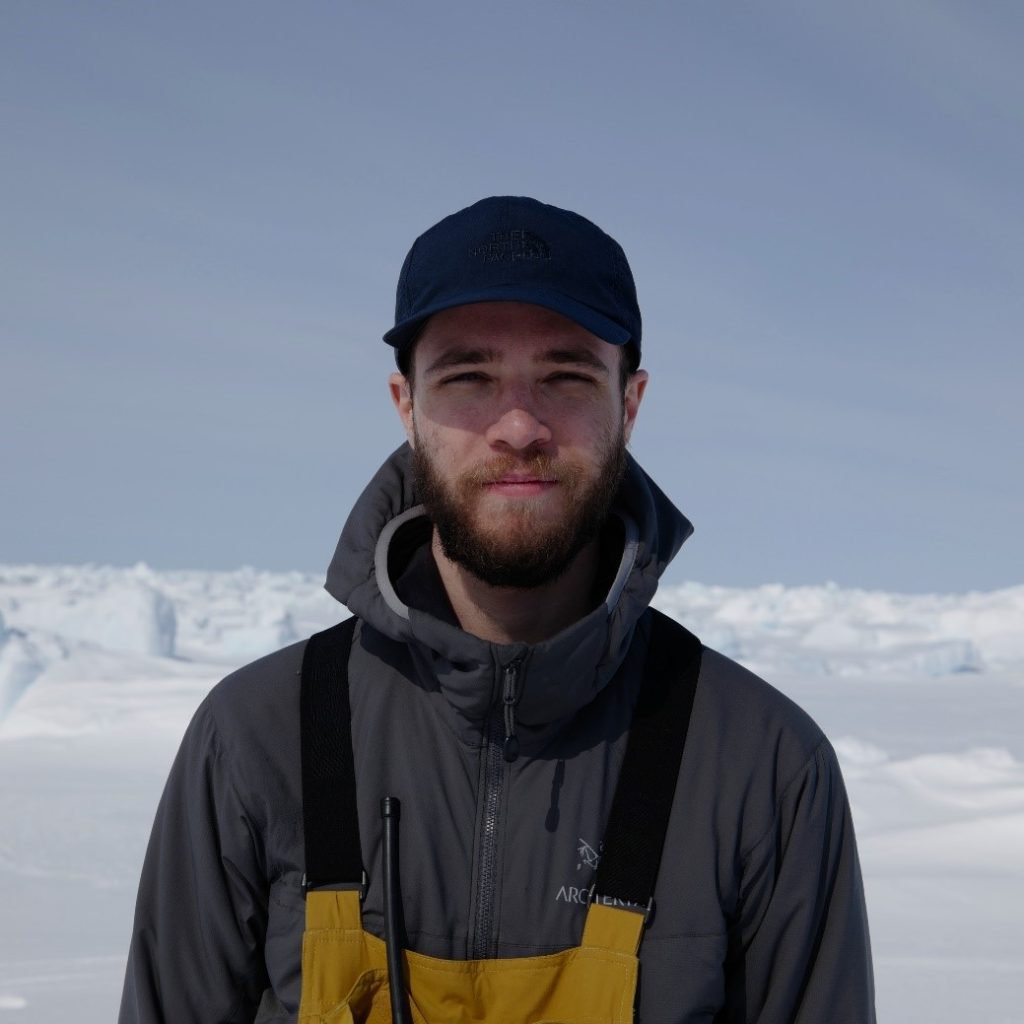

Hi! My name is Nick Paroshy. I study polar bears at the University of Alberta. I’m learning all about how polar bears move through the Arctic Circle. Because of climate change, some of the sea ice that polar bears depend on to get around and hunt for their prey is melting. I’ve been studying polar bears who live in two areas of the Arctic: one called the Beaufort Sea, and the other called Hudson Bay. This will help me and my team better understand how polar bears move on the sea ice. The more we know about their movement, the more we’ll be able to help them adapt to climate change.

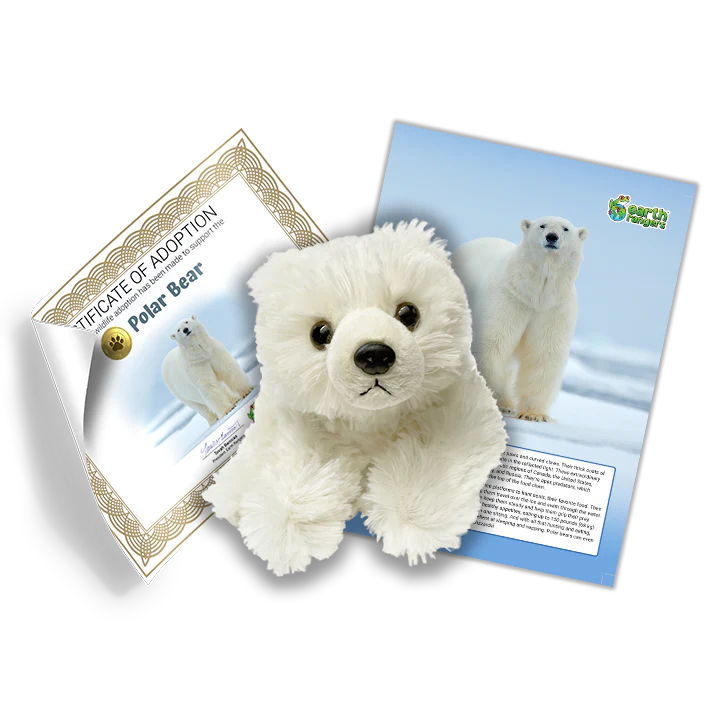

When you adopt a polar bear from Earth Rangers this year, you’ll be supporting me as I track polar bears and work through a lot of complicated math to find patterns in their movements. You’ll receive a cuddly polar bear stuffie with soft white fur, along with an adoption certificate, a trading card, and a poster for your locker or your bedroom wall.

Check out the adoption section in the Earth Rangers App to learn more, and check out these cool photos we took while tracking polar bears!

How I Research Polar Bears in the Beaufort Sea

This photo was taken from a helicopter high up above the ice where the polar bears live. Although they may look cute and cuddly, polar bears are wild animals, and it’s unsafe for human beings to get close to them. That’s why polar bear researchers like me don’t walk around looking for bears–we scout them out from the safety of a helicopter.

Don’t worry–this polar bear is safe and sound, just unconscious – kind of like being in a deep sleep! In order to track polar bears and learn more about their movements, we need to tag them with tracking devices. These tracking devices let me use a computer to follow them around.

But remember: polar bears are wild animals, and it’s not safe for human beings to get close to them. We can’t ask a polar bear politely if we can tag it. Instead, we tranquilize the polar bear. This means that we give the bear a dose of medicine that sends it to sleep for a little while–just long enough for us to tag the polar bear and leave safely.

First, from the safety and comfort of our helicopter, we aim a dart at the polar bear. When we’re sure that the dart will land safely on the polar bear, we send it out. We watch the dart fly out and connect with the polar bear’s skin. Then we wait as the medicine makes the bear calm and sleepy enough to lie down, close its eyes, and become unconscious. At that point, we land the helicopter and begin to measure and tag the polar bear so we can track it.

Here is a photo of me measuring a polar bear’s head. We need to collect all sorts of measurements to compare bears to each other. Once we have all our measurements, I fit the tracking device securely on the polar bear. Then my team and I return to our helicopter and fly off to find another bear.

Bears come in all sizes. They can be kids or teenagers or parents. Some bears are huge! See how big this bear is compared to me! Look at my hand next to its paw! Polar bears have very large claws which can seriously hurt humans, but help them hunt seals.

Check out this photo of a ringed seal that I saw during my journey! We call them ringed seals because of the circular patterns on their fur. These creatures happen to be polar bears’ favourite food. If there aren’t enough ringed seals, then polar bears don’t have enough to eat. That’s why it’s important for us to conserve ringed seals along with polar bears.

Now That I’m Home from the Arctic

Studying polar bears doesn’t mean that I spend all my time flying over the Arctic Circle in a helicopter! Once I’ve tagged enough polar bears with tracking devices, I come home and study the data that they’re sending me. It’s my job to find patterns in the data, talk about what I’m finding with other scientists, and write down everything that I’ve learned.

Right now, I’m focusing on putting all of my research on polar bears together into a very long piece of writing called a thesis. When that’s done, I’ll publish it in a journal. This isn’t the kind of journal that you hide under your mattress to keep your secrets safe from your little siblings–it’s a magazine that scientists read to learn about the discoveries of other scientists.

I’ll also defend my thesis in front of a group of my teachers. They’ll ask me all kinds of questions about polar bears, about my research methods, and about everything I’ve discovered. When that’s over, I’ll graduate with a Master’s Degree in Science.

If you want to research polar bears when you grow up, you might go through this process someday, too! But whether or not you decide to become a scientist like me, I hope that you’ll stay interested in polar bears, climate change, and the Arctic Circle. We need kids like you to stay curious and compassionate so that polar bears and their icy habitat will be safe for generations to come.

So cute and adorable

It sounds amazing.