American eels (Anguilla rostrata) are a type of fish with a long body that looks like a snake. These amazing animals love to travel. They live in many different places throughout their lifecycle including both salt and freshwater habitats. In fact, these amazing eels have one of the most diverse uses of habitats of any fish species! American eels can even absorb oxygen through their skin as well as their gills, which allows them to travel briefly over wet grass or mud.

Their lifecycle begins in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean in a spot called the Sargasso Sea. From here, American eels move in through estuaries (habitats where fresh and saltwater meet) and into rivers and lakes. Their range is really big, extending as far north as Greenland and as far south as Brazil! When the eels are full grown, 5 years for males and up to 25 years for females, they return to the Sargasso Sea to spawn (leave their eggs). The eel’s lifecycle ends after spawning, similar to Pacific salmon. The next generation will then begin their long migratory journey.

Did you know…? American eels can cover their bodies with a mucous layer which makes them almost impossible to hold, that’s where we get the saying ‘slippery as an eel’!

In Ontario, American eels are considered endangered. They face many threats; one of the biggest is the construction of hydroelectric dams. These dams block American eels from swimming upstream as they try to migrate to their habitats. To help these slippery animals get over the dams, Ontario Power Generation uses a very creative solution.

Jumping the Dam

How do you get an eel over a dam? With a ladder of course! Thanks to a series of chutes that zigzag up the dam, eels can safely migrate over power plants. Eels that enter the Gulf of the St. Lawrence and migrate upstream through the St. Lawrence River have to cross two major hydroelectric dams. Since 1974, eels that make this journey get a little help thanks to a ladder operated by Ontario Power Generation. This ladder was really successful, so in 2002 three more ladders were added along the St. Lawrence River.

Eel Count

Ontario Power Generation monitors the ladders using electronic counting equipment, which sends an email to the operators at the power station when an eel uses the ladder. It’s like the eels are sending an email to say ‘hi’ to the Ontario Power Generation staff as they pass through! Thanks to this initiative, more eels can safely travel through their migratory path; in the last four years between 11,600 and 26,000 eels have used the eel ladder.

If you were an eel, and could use any mode of transportation, how would you get over a dam? Paraglide, rocket skateboard, hot air balloon…. Leave your suggestion in the comments section below!

Moulting is a very intense process and can be very taxing on birds. It takes a lot to of energy (and food) to grow new feathers! During this time, the birds will add more protein, calcium and iron to their diet. They also move around less because it is difficult for a bird to fly very much when it is growing new feathers. Even though moulting is tough for birds, growing a new set of feathers is really important. After all, feathers are vital for regulating body temperature, protection and camouflage, attracting a mate and, of course, flying!

Moulting is a very intense process and can be very taxing on birds. It takes a lot to of energy (and food) to grow new feathers! During this time, the birds will add more protein, calcium and iron to their diet. They also move around less because it is difficult for a bird to fly very much when it is growing new feathers. Even though moulting is tough for birds, growing a new set of feathers is really important. After all, feathers are vital for regulating body temperature, protection and camouflage, attracting a mate and, of course, flying!

In 1989, sea level pressure in the Arctic dropped sharply. When sea level pressure changes like this, it can cause a change in the flow of air and water. Warmer, more salty water from the North Atlantic Ocean started flowing into the

In 1989, sea level pressure in the Arctic dropped sharply. When sea level pressure changes like this, it can cause a change in the flow of air and water. Warmer, more salty water from the North Atlantic Ocean started flowing into the

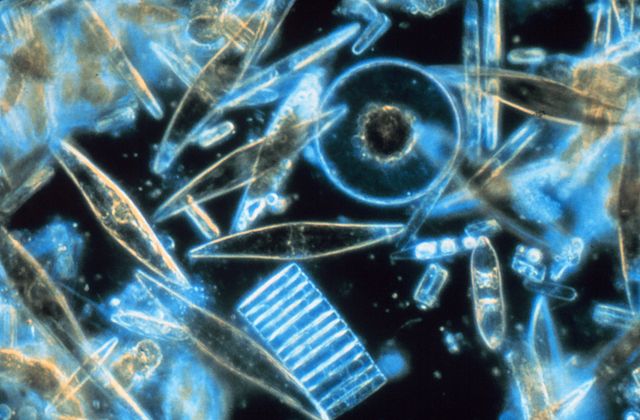

As our oceans change due to climate change and pollution we are creating the perfect environment for big populations of

As our oceans change due to climate change and pollution we are creating the perfect environment for big populations of  Save the Reefs!

Save the Reefs!