Get all of your eco-terminology in this glossary, filled with definitions for everything from conservation to biodiversity!

At Risk:

A species is described as being at risk when it is in danger of becoming extinct. Species that are either endangered or threatened are considered to be at risk.

Biodiversity:

The variety of life forms found within an ecosystem or over an entire planet. Biodiversity is used to measure the health of an ecosystem—the greater the variety of living things in an ecosystem, the healthier that ecosystem is thought to be. It is important to remember, however, that biodiversity will vary naturally from place to place, with healthy ecosystems in Polar Regions typically having lower biodiversity than healthy tropical ecosystems, for example.

Breed/breeding:

Organisms are said to breed when they reproduce or create young. Sometimes, in order to protect a species of endangered animal, scientists will create a captive breeding program. These programs provide ideal breeding conditions for animals living in zoos or other facilities so that the young produced can be released into the wild. Captive breeding programs have helped save animals like the spotted frog and the black footed ferret from extinction.

Conservation:

The management of natural resources in order to protect biodiversity. Usually this involves studying and protecting species and their habitats, as well as the ecosystems with which they interact.

Endangered:

A species is considered to be endangered when it is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild. Scientists determine if a species is endangered by considering how many individuals are left in the wild and how quickly their numbers are decreasing, as well as the size of the area in which they can still be found in the wild. Species whose numbers in the wild are decreasing quickly and who are only found over very small areas will probably become extinct soon unless action is taken to protect them—these species are therefore considered to be endangered.

Extirpated:

A species is said to be extirpated when it has become extinct in a specific area but can still be found in the wild in other parts of the world. For example, grey wolves became extirpated from Yellowstone Park in 1926 because of over-hunting. Luckily, wolves were still found in other parts of North America, and in 1995 a group of 14 wolves from Alberta were released back into Yellowstone to repopulate the area. Sometimes extirpation will be referred to as a “local extinction”.

Extinct:

A species is said to be extinct when there are no more individuals of that species living anywhere on Earth. Organisms that only exist in captivity may be said to be extinct in the wild. A species may become functionally extinct when there are no longer any individuals capable of breeding and creating further generations.

Geolocation:

The process of finding an animal’s location on the globe using a variety of techniques. When studying wild animals, scientists can use many different types of technology to keep track of the movements of individuals or entire populations. Radio transmitters on collars, for example, can be tracked with receivers on trucks or airplanes, or even onboard satellites.

Habitat:

The area or environment in which a population of organisms normally lives is called its habitat. Habitats can vary greatly in size, and may sometimes be fragmented or patchy. A habitat becomes fragmented when it is broken into chunks that are no longer connected to each other—for example, building a road through the middle of a forest breaks that forest in two, creating a fragmented habitat. Since habitats provide everything that organisms need for survival, the loss or change of a habitat can have an enormous impact on the survival of those organisms.

Invasive Species:

A species that has been introduced to an ecosystem from another part of the world and is having a negative impact on the health of the environment into which it has been released. Invasive species can destroy habitat and disrupt food webs, and can sometimes introduce diseases and parasites as well. A famous example of an invasive species is the European rabbit, which was introduced to Australia in 1859. With no natural predators, the rabbits quickly spread across the eastern part of the country, devastating local ecosystems by eating too many native plants and outcompeting native mammals for resources like food and water.

Luminescence:

Luminescence occurs when light is produced by an object in a way that does not involve heat. Think of it this way. When your stove element gets hot it glows red, but this is due to heat, so it is not luminescence. In Polar bear guard hairs, the beam of light hitting the inner surface of the hair causes light to be given off but heat is not involved, creating luminescence.

Native Species:

A species is described as being native to an area if its presence there is the result of natural processes, and not as a result of human activities. Sometimes a native species may also be referred to as an “indigenous species”.

Organism:

An individual life form that may be a plant, animal, fungus, protist or bacterium.

Population:

The number of individuals of one species living within a certain environment. The population sizes of different species living together in an ecosystem will naturally vary over time. Some species, such as leaf cutter ants, will tend to naturally have very high populations, but others, like blue whales, will tend to have much smaller populations.

Species:

a species is generally considered to be a group of individuals that are capable of breeding with each other, having young that are able to produce offspring of their own, and that do not breed with different groups of other individuals. Defining a species can be a challenge, however, because there are exceptions and special cases in the wide world of biology.

Threatened:

A species is considered to be threatened if it is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the threats the species is facing in the wild. Some organizations will also use the term “vulnerable” to describe these species.

Earth Rangers is a non-profit organization that works to inspire and educate children about the environment. At EarthRangers.com kids can play games, discover amazing facts, meet animal ambassadors and fundraise to protect biodiversity.

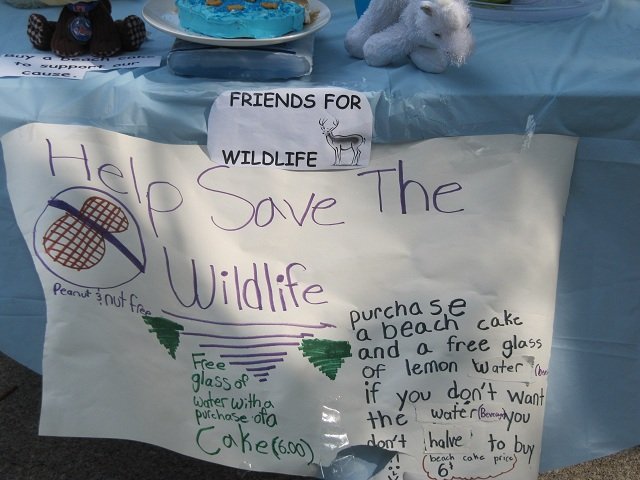

We heard of the Bring Back the Wild program through our school. Last summer we started fundraising by selling cakes on our street. We baked and decorated beach cakes to fit the summer season. After fundraising for a day, we created a commercial to send to family and friends. Everybody was so generous. Some people even donated extra money to support the cause!

We heard of the Bring Back the Wild program through our school. Last summer we started fundraising by selling cakes on our street. We baked and decorated beach cakes to fit the summer season. After fundraising for a day, we created a commercial to send to family and friends. Everybody was so generous. Some people even donated extra money to support the cause!

Hi, my name is Nasim and I am 11 years old. I LOVE animals so much. My family has travelled to many cities to see as many animals as we can. My favourite animal is the

Hi, my name is Nasim and I am 11 years old. I LOVE animals so much. My family has travelled to many cities to see as many animals as we can. My favourite animal is the

Bees have a BIG responsibility because they are the most important group of pollinators on Earth.

Bees have a BIG responsibility because they are the most important group of pollinators on Earth.  Fungi are one of the most important

Fungi are one of the most important

It might make you sad when one animal eats another one, but the so-called ‘circle of life’ is very important for keeping populations at a manageable size. When natural predators go missing, its prey can reproduce uncontrollably. The sea otter is an excellent example of this; it feeds on

It might make you sad when one animal eats another one, but the so-called ‘circle of life’ is very important for keeping populations at a manageable size. When natural predators go missing, its prey can reproduce uncontrollably. The sea otter is an excellent example of this; it feeds on  When

When

a) Water

a) Water a) Leave your electronics on

a) Leave your electronics on a) Make your lunch litterless by using reusable containers

a) Make your lunch litterless by using reusable containers a) Kitchen

a) Kitchen a) Walking

a) Walking Fill in the blanks

Fill in the blanks a) Buy products with cat pictures on them

a) Buy products with cat pictures on them a) Tall plants

a) Tall plants a) Shark fin soup

a) Shark fin soup